Past Projects

Soundings

The HARK Soundings project was an exploration of listening across ‘deep geological time’ through the sounding of stones. A paper called ‘Live Listening is attached below. The stones for this exploration were collected from across the geology of Scotland. We then constructed an untuned Lithophone from these stones.

A performance day was designed for 50 participants to explore the geological history of stones, and to prepare for the performance through a mediation on listening. In order to sound the stones we invited a percussionist, Alex Waber and a digital composer, Alastair Macdonald to collaborate on a semi improvised performance of playing the Lithophone, Alastair recording Alex playing and in real time responding to the sounds digitally. The participants were placed in a circle and surrounded by 15 speakers. Participants were first led in a sound meditation as preparation, A lecture ‘Sermon in Stones’ was given after the performance. The recording below was developed further into a video piece called Cosmosis presented here.

Ringing Stones and Lithophones

Stones have been ‘sounded’, used in ritual and in musical contexts for millennia. Lithophones, tuned stones constructed as pitched musical instruments, have also been constructed. We decided to create a geological time series of stones from across Scotland and explore their acoustic qualities. This time series spans an unimaginable time-frame, from 3 billion years ago in Precambrian strata to Tertiary and Quaternary rocks. Just as the light of stars takes ‘light years’ to arrive here, in the stones we hear the deep ancient resonance of the planet, and can resonate with it. We intend to create the sound of geological time as it has lain dormant in the Scottish landscape.

The zig-zag route of our fieldwork, gathering stones, crossed the six major fault lines of the geology of Scotland, starting from the oldest Outer Isles Thrust/Moine Thrust of Lewisian rock and granite, coming south crossing the Great Glen Fault, extracting and collecting each rock type.

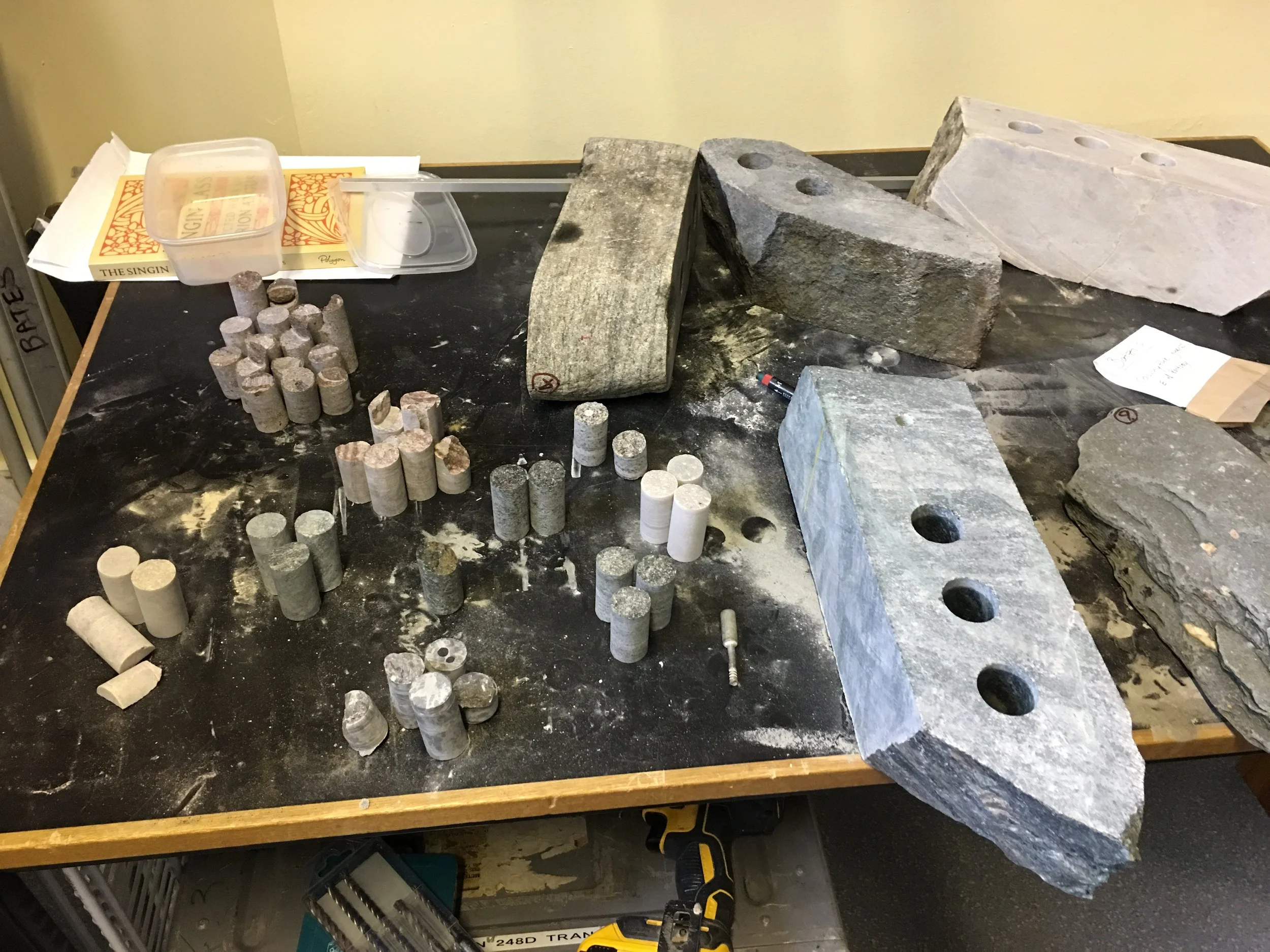

Stones exist in different states. Natural and unweathered stones are still attached to the earth. Weathered stones have become detached and transformed by the elements. We called these ‘natural’ and ‘honed’ stones we continued the honing process with a set of the natural stones. This entailed experimentation in cutting, drilling, hanging and striking the stones with stone itself, wood and metals. We explored aspects of sound resonance and amplification by striking the stones with various materials in the Silo and recording their sounds. These can be heard in samples below.

We constructed a ‘Sound Installation’ a Natural Stone Lithophone, which hung the first time series of natural stones, and also hang a series of ‘honed’ stones taken from the natural series. These were played in performance by a percussionist, Alex Waber. With the digital feedback recording of Alaisdair MacDonald.

We were not attempting to produce a pitched/tuned Lithiophone as a musical instrument. We attempted to sound a time series of natural stones, amplify their qualities for performance and feel their vibrancy. We are not the first project to try to make art with stones via a constructed ‘lithophone. An example of sounding stones by Marten Bondestam can be found here: https://youtu.be/TOmel9EtL-E. Our project therefore sits as it were historically between the archaeological discovery of the use of stones for sounding and the later contemporary fashion for the building of tuned instruments made of stone. This history is relevant.

As Neil MacGregor, sometime Director of the British Museum pointed out, “for a million years the sound of making hand-axes provided the percussion of everyday life”. The Ringing Stone of Tiree in Scotland and other such stones have been found to ‘ring;’ when struck, and there is evidence that rocks have been systematically struck, the hammer indentations being visible, for their sound and resonance, possibly for ceremonial ritual, for communication, or as an early form of music. Rock gongs can be found in the landscape in parts of Africa, (Nigeria, Uganda, and Sudan) and India. Stones sound in landscape and also in enclosed spaces. There are speculations that some of the 34,000 year-old caves with hand drawings that some of these are positioned at nodal points in the cave structure to enhance the reach of any sound made at those points. Stonehenge has been thought to have been ‘sounded’ as part of its construction: https://gizmodo.com/is-stonehenge-actually-a-giant-musical-instrument-1539942048

Sixty years ago archaeologists unearthed sets of stones in Vietnam which were grouped by pitch. Some of these finds are 3,000 years old. Dan da, a tuned lithophone resembling a xylophones are still used in Vietnam. In Togo, Central Africa, small flat stones emitting different notes are laid on the ground and struck with another smaller stone in a ritual performance that relates to the change of seasons. Chime bars have been used in ritual and court music. These originate in China, known as bian q’ing and are made with marble and jade and suspended on a frame. We intend to follow this method of suspension on a forged metal frame. In these cases the pitch is determined by where the stone is struck with a hammer, thickness being a determining factor. Such stones may also be found in Korea and Japan. (insert Chinese illustration). The Vietnamese stones were researched by Mike Adcock and Ingrid Lund and their explorations can be found on lithophoes.com.

Stone instruments have been created in the UK. I have noted the Lake District slate as the material for a lithophone. In 1785 Peter Crosthwait collected rocks from Skiddaw that had resonant ringing qualities. Pieces of slate could be split and chipped to be tuned and then by covering with salt and tapping to find the place to which it runs the slate was then bored at that thinnest spot and suspended. His xylophone was followed by a larger instrument the ‘Rock Harmonicon’ built by Joseph Richardson over thirteen years and by William Till whose stone instrument toured the USA. The tuned slate of the Lake District which has been played by Evelyn Glennie. Two newly built lithophones were presented in 2010 in the former home of William Ruskin built by Marcus de Mobray in Lakeland stone and by Kia C.Ng. The latter uses some electronic sensors which enhance its qualities. We intend to experiment with these possibilities with untuned natural stones. Some tuned lithophones introduce quarter and eighth tones and these have been exploited by Jesse Stewart using only marble. Contemporary international activities can be found on-line at lithophones.com. The sounds produced by Pietro Pirelli by touching, scraping, sawing, plucking and striking stones can be heard by the link below, and the experience of listening to these sounds and the playing can be approached in similar ways to that described as an engagement with Reich’s Drumming, which I describe above – that is how we allow these sounds to resonate in or bodies. https://youtu.be/p5Q5bW3bYMM.

Stones are not only implicated in sound and resonance by being struck, but also by constituting spaces in which sound travels, reverberates and echoes. The architecture of Romanesque Churches, with flat solid walls, produces surfaces and volumes are designed to amplify, spread and maintain sound. Stone is often the material that constitutes exceptional acoustic environments, as in Greek amphitheatres and in the Silo in which we will perform. We are therefore exploring stones sounded in landscapes and in acoustic spaces themselves made of stone.

We are exploring the acoustic resonance of natural stone and working with the honing of those stones to amplify their qualities. Only then will they take their place in an installation.

Below are some further links to stones being sounded.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7I5fg2UyjE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u8fqnipmUPA

https://www.bellperc.com/collections/gong-tam-tam-hire/products/thai-gong

Sermon in Stones

Earth history is a four and half billion-year-long chronicle of creation and destruction, a story of a planetary Yin and Yang. The interconnectedness and complementarity of the Earth system operates on all scales across all time: plate tectonics, a tireless global cycle of forming and breaking of continents and oceans driven by the radioactive decay of the breaking and shaping of atoms in Earth’s interior; the thriving and dying of life as represented in myriads of evolutions and extinctions over billions of years fuelled by the Sun’s radioactive energy; a cycle of Earth system change that shapes and reshapes the planet that we, and all life, inhabit, a consequence of the vagaries of those geological processes.

Scotland’s archive of that history is unparalleled. The country who produced the scholars whose collective intellects built the foundations of the science that enables us to interrogate and understand our planet is, perhaps unsurprisingly, also the country that packs the most geology hectare-by-hectare of anywhere. Today we will experience that history as a series of geological vignettes, each preserved in a rock that comes from Scotland.

A rock is Earth’s record of her life, written in a language decipherable by the geologist. MusicPlanettranslates that language into sound, and will place that sound in the 3 billion years of Earth history that Scotland retains. We humans are but the very last (in time and space) sentence of this ongoing story but in an incredibly short time we have come to dominate Earth, profoundly, disproportionately and unwittingly veering that story onto a path with unknown but no doubt lasting impact.

Sit back, enjoy and contemplate the Sermons and the Songs of the Scottish Stones.

3000 million years ago: Lewisian gneiss

The ‘basement’---and, like the foundations upon which buildings are built, these rocks are the deep roots of some of Earth’s most ancient mountains. For 3 billion years they have been twisted and deformed yet remain the cornerstone of continents and a lasting testament to the antiquity of plate tectonic processes.

2000 million years ago: Loch Maree Banded Iron Formation

The greatest environmental crises ever, the poisoning of Earth known as the Great Oxidation Event is preserved in the alternating red and grey rocks known as Banded Iron Formations. The origin of that profound and complex process of photosynthesis liberated free oxygen, in effect, a never-ending stream of pollution that placed Earth on an irreversible trajectory that transformed her from an anoxic to an oxic planet.

1000 million years ago: the Torridonian Sandstone

Mighty Quinag, iconic Suilven, jagged Stac Pollaidh, all owe their origin to the ancient rivers that flowed across Scotland and carried detritus to a faraway sea. The supercontinent of Rodinia was forming and broad rivers flowed off the rising highlands forming plateaus and plains, one of which would become Scotland. Simultaneously, the evolutionary transition from sea to land had begun with simple algae colonising the edges of land surfaces.

700 million years ago: Port Askaig Tillite

Earth was plunged into the greatest, most extreme ice age ever, Snowball Earth …life clung to existence in ephemeral puddles and beneath cracks in the ice and along deep-sea vents---tens of millions of years of ice, with oceans frozen from the poles to the equator and howling winds.

540 million years ago: the Piperock and the Durness Limestone

Scotland is now in the tropics, Snowball Earth has melted long ago, the oceans swarm with animals, and the seas transgress across all land surfaces as beaches give way to bays and then shallow marine platforms, in effect, a Scottish Bahamas.

460 million years ago: Caledonian granite

For 4 billion years, Scotland and England remained geologically sovereign. Then, as the ancient oceans closed and continents collided, a geological act of union occurred, forming the Caledonian Mountains from North America through northern Europe and at their heart was granite, the same granite that defines much of Scotland’s present-day mountainous backbone.

400 million years ago: Devonian Old Red Sandstone and Flags

The cycle of rejuvenation, the cycle of decay, mountains form and mountains fade away…such was the fate of the Caledonian Mountains, eroded to their granitic roots and mantled by an apron of sand and mud that was to become the red building stones and grey paving stones of many Scottish towns and cities.

300 million years ago: Carboniferous sandstones and coals

The muscle of the Industrial Revolution was fed on a gluttony of coal that formed in the lush swamps and thick forests dissected by wide rivers that flowed through a tropical Scotland. Reptiles had taken their first steps onto the ladder of evolution, insects were the size of birds and the ancestors of mammals were forming their budding branch on the tree of life. The continental collisions that would lead to the formation of the supercontinent Pangea were reaching their crescendo.

50 million years ago: dolerite from Rhum

Pangaea was fragmenting into the continents that form today’s present-day plate tectonic snapshot. Some of the final tearing apart creates huge volcanoes and rupture Europe from America, forming the North Atlantic ocean and, for us, orphaning Scotland from the land mass that had been her home for 3 billion years. (a form of music that suggest separation and a drifting apart from one another)

3 million years ago: quartzite from Ethiopia

The earliest evidence for stone tools comes from marks on animal bones in the Lower Awash Valley Ethiopia at around 3.4million years ago. Hard, dense material lying around river courses was worked (chipped) into rough cutting shapes.

800 thousand years ago: flint from Aberdeenshire

The last 30 million years are marked by a change in global climate that resulted in permanent ice caps at the poles and cycles of cooling causing glaciers to extend over northern land masses. The vast ice sheets and glaciers moved rock hundreds of kilometres from their origin scattering them widely when the climate warmed again.

12 thousand years ago: flint from the North Sea

As the climate warmed following last glacial maximum (at 27 thousand years ago) hunter-gatherers moved across a dried out North Sea and walked into Scotland.

6 thousand years ago: flint from Fife

Increased population across “island” Britain, a change to farming and the building of permanent residences necessitated the invention of new tools for taming the wilderness. With an exponential pace of change the influence humans have on the Earth ensures that the lands will never be the same again. The Earth begins to run out of control and descend once more to the chaos of the beginning of time.

Stones use in the construction of the Lithophone

Lewisian gneiss

Loch Maree Banded Iron Formation

Torridonian Sandstone

Port Askaig Tillite

Piperock

Durness Limestone

Caledonian granite

Devonian Old Red Sandstone

Carboniferous sandstone

Rhum dolerite

Ethiopia quartzite

Aberdeenshire Flint

Fife Flint

Performers

Alex Wäber was born in 1979 in Basel (Switzerland).He completed his studies at the University of Music in Basel in 2003. This was followed by two post-graduates at the Music Academy in Lucerne. Since 2001 he is solo timpanist in the chamber orchestra basel, and solo timpanist in the Gstaad Festival Orchestra. In addition, he has been a permanent member of the Sinfonieorchester Basel for around 20 years and a teacher at the Basel Music Academy. He played as a drummer and timpanist in the most important concert halls throughout Europe, Asia and South and Central America.

Tony Prave is a geologist who specialises in studying pivotal periods in Earth history. His work has taken him from the Artic north of Russia to the deserts of southern Africa and the American southwest and he is considered to be one of the leading field geologists of his generation. Tony’s expertise lies in reconstructing ancient environmental settings and his work has ranged from how Earth became an oxygenated planet more than 2 billion years ago, to documenting the conditions that drove severe climate change in Deep Time, to assessing the impact of supervolcanoes on Earth system functioning. Tony has been at the University of St Andrews for 22 years and currently is Professor and Head of the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences. Prior to that he was, for 10 years, an Associate Professor at the City University of New York.

Alistair MacDonald is a composer, performer and sound artist. His work draws on a wide range of influences reflecting a keen interest in improvisation, transformation of sound, and space. Many of his works are made in collaboration with other artists from a range of media. It explores a range of contexts beyond the concert hall, often using interactive technology.Current and recent projects include music for the 1922 film Nosferatu; a collaboration with Belgian dance company Reckless Sleepers; Strange Rainbow, a live electroacoustic improvising duo with Scottish harp player Catriona McKay, and The Last Post with trumpet player Tom Poulson and director Susan Worsfold commissioned by the St Magnus Festival and performed at the 2017 Edinburgh Fringe. He has also been working with Carrie Fertig, on pieces for glass percussion, electronics and live flame-working. Le Sirenuse (with percussionist Stu Brown and film maker Rob Page) was selected for the Royal Scottish Academy Open Exhibition 2015.Other recent works include The Imagining of Things with Brass Art (video and audio installation) for Huddersfield Art Gallery, and Mitaki (string quintet and live electronics) for the Scottish Ensemble.

Silo

The Cupar Silo was built in 1964 as a bulk sugar store for the adjoining sugar beet factory, its short life ended in 1971 when the whole factory was closed and was then used for grain storage until the late 1990’s when no longer viable. Having remained empty for a number of years, in 2008 the 197ft silo began a new life as an experimental arts venue. Since then it has hosted several arts events including installation, film, performance, dance and experimental sound work. The Silo is now managed by a charitable organisation,

Hark Collective have used the Silo acoustic space on three occasions.

In the first visit we experimented with the acoustic qualities of the space. The resonance was remarkable with the overall ‘echo’ effect being 12 seconds. We also felt that the sound moved around the space and was particularly interesting close to the circular walls. The players than improvised and in doing so were able to heard how the long duration of sounds and notes could add to a form dense harmonic textures. At the same time solo instruments were given a duration and edge which required certain approaches to playing. The outtake were remarable and were edited into the album HARK at the Silo which is available on Spotify or from this website. The instrumentation was cello, sax, violin and voices. The track Polyphony using voices in a rendition of a Renaissance piece Sicit Cervus by Palestrina reflects the influence of the playing of sax players Jan Garbareck and Ralph Imbert.

In the second visit in the project Soundings improvisation was provided by conch and percussion. 50 participants spread around the walls were invited to bring a sound and these were sounded into the texture of the improvisation. It should be said that the silo is completely dark with little lighting and this gives another dimension to the experience.

In the third visit a screen and dance floor had been installed. We played with projections of video and performers in front of the screen and with the effect of shadows. Some of these are presented here and in particular the performance by Claudia Labaou (voice) and Claire Garabedian (cello).

The outtakes from all these visits has provided a store of material that finds its way into other projects as sound-tracks.

Listen to Silo on Apple Music or Spotify

Music Poetics & an Ethnography of Listening

Music Poetics is the term we use for a genre of writing about sound and music. This genre is an attempt to describe evoke and share the listening experience in another medium, usually, but not always in words. There are examples below — group responses to listening to ‘In Earth’ by Errollyn Wallen, and personal reflections on listening to the cello album of Leila Bordreuil ‘Not An Elergy’. A good example of this genre can be found in ‘Ways of Hearing: Reflections on Music in 26 Pieces’ (2021. Ed. Burnham, Seltzer & Von Moltke. Princeton UP) and some of the reflections in that collection include a photographic essay, poetry as well as prose.

In HARK we developed this ‘poetics’ approach through the Listening Groups: from recording verbal responses to the music; collating the results across groups; by content analysis we identified themes, metaphor clusters, strands of imagery; and we wrote these into a script. A dialogical process of distillation was developed using the script and a single person (the ethnographer JHLR) wrote a ‘prose poem’ which was further refined into a ‘libretto’ and written into the score of the music (see the images above). This was performed as a co-procuctive art-work with a twelve string orchestra (conducted by Bede Williams) with the ‘libretto’ being spoken by two trained voice performers in a ‘conversation’ over the relevant music. This methodology was used for all 4 movements of the composition ‘Photography’ by Errollyn Wallen. Listeners’ creative output resulted in the performed Ethnography of Listening. Thos project exemplifies the practice of emphasis in create work. This a transfigurative process whereby an art-work, by reception by others, stimulates the creativity of others such that they produce another art-work . Ekphrastic practice is discussed in the longer version of the paper below: Ethnography of Listening. The project is documented in the papers below and you can replicate our method for yourself — listen to Photography first, reflect on the images, words, sensations that arise, then listen to the performance of the Ethnography of Listening. All of this you can do from the audio files below.

The Ethnography of Listening Project was written up and presented at the FASS Conference at the Open University. A short version and full version of that paper can be found below. Here is the Abstract of the paper:

This paper explores the expression of listeners’ significations after listening to a piece of orchestral music. It describes the dialogical creation and performance of an ethnographic evocation of the experience of listening to a particular pice of music – a Performance Ethnography of Listening. 40 members of 4 Listening Groups listened to a four-movement piece for string orchestra “Photography” by Errollyn Wallen and gave their responses which were taped and transcribed. A Source Text was created from the raw responses from which was written a Performance Script for two ‘voices’. The script was set within the time signature of the piece. A Listening Event was designed to enable an audience, including the Listening Group members, the composer, the conductor, the ethnographer, and the ‘voices’ (60 people) to listen to, and discuss a ‘triptych’ performance of the work – the central panel being the performed ethnography with the music the side panels being a performance of the music alone. This paper describes the ethnographic process, includes the Performance Script and audio examples of the performed ethnography. It theorises our practice in terms of the work of: Nicholas Cook (1998) on the relationship between words and music; Anthony Gritten (2017) on intermedial practice; Lawrence Kramer (2011) on criteria for ekphrastic practice; and in the light of existing explorations in the HARK Project on, listening habitus, and listening repertoire – ‘auditory play’.

The Documents and Sounds below are ordered to illustrate the subjects in this introduction.

Documents

These are papers written as Music Poetics

Music Poetics (1): Errolyn Wallen’s “In Earth” Listening Responses.

Music Poetics (2): Full Transcript of “In Earth” Responses.

Music Poetics (3): Liela Bordrieul’s “Not an Elegy”.

These are papers concerning the Project structure and the Listening groups:

Listening Groups: Structure, Composition and Program.

Listening Groups: Listening Curriculum.

Listening Research: Pilot Report.

Notes for Listening: Session 5

These are papers concerning the ethnographic work with the piece Photography:

Listening Notes for: Errollyn Wallen’s "Photography”.

Precis of Paper: An Ethnography of Listening.

Full Paper: An Ethnography of Listening.

These are papers theorising about Listening:

Repertoire of Imaginative Auditory Play.

Sounds

The audio links below provide the four movements of Errollyn Wallen’s ‘Photography’ and then the text of the ethnography of listening performed with the music. Listen to the original piece first, then listen to the images and metaphors which our listening group members used to express their responses to the movements when performed with the music.

Also below in Music Poetics (3) the original album by Leila Bordrieul ‘Not An Elegy’ can be found on Boomkat in download or vinyl versions.

Finally I reproduce here (above on a link) a schema of listening modes that we have noticed in responses in the listening groups. These listening modes are often overlapping and are not mutually exclusive but suggest that our listening repertoire is focal at times and immersive at others and that attention oscillates with reverie. These modes map onto the perceptual-cognitive framework proposed by Iain McGilchrist in his work on ‘Attending’.

Music and the Sacred

There are a series of connections between the HARK explorations and a domain of experience that we might call ‘spirituality’.

Music and the Sacred: A Quick Look.

The attention we give to the video/sound art-works that we have created draws on deep traditions of ‘attending’. These have been explored by anthropologists particularly in the context of ritual studies. The practices that we might develop in working with our materials concern those of meditation, contemplation and various postures of (in)attention. We are able also to be reflexive — we can develop and deepen our practices of attending and also notice how we have been attending in the past, and how our experience is changing.

he knowledge-practice concept of ‘transfiguration’ in the gestalt of our sound and vision is the sensory aspect of the way our assumptions, preconceptions and habits are able to be suspended. This suspension makes space for us to notice other features and qualities and these subtle changes are what I ref to as ‘transfigurations’. We can also to notice what arises in our imaginations when such (head/heart/body) spaces are created.

This space is often ‘apophatic’ that is, it enables significance, value and curiosity to thrive without the need to put the ’experience’ into words or other medium immediately, or at all. I quote mark the word ‘experience’ because formally it is moot definitional matter as to whether one can have an experience that is entirely outside/beyond language. There is a space also between what we mean by sensation and experience.

This process is also connected to a key theme of the HARK project which is the engendering of creativity and expression, particularly in improvisatory, embodied, shared ways — we have used the concept ‘ekphrasis’ to describe this creative process and outcome.

These practices radically reframe our sense of the conventional binary between ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’, and ‘inside’, ‘outside’, and the relationship between the disclosure of the world as it is and our constructions, imaginations and creative rendering of it. We have explored these connections in some Working Papers, Current Projects and some ideas for future work. We would be interested to respond to anyone who is interested in taking these ideas further.

The Workshop on Music and the Sacred produced some Working Notes and a playlist and they can be found here below. As an introduction to what is a long playlist that goes with the text below, you can first listen here to some initial calls to prayer, showing the simplicity of the sounded invitations to enter a meditative space:

The Beyond Babel prayer project was a sound exploration of the Lords Prayer recited by 16 different language speakers in the mother tongue in which they had learned it. This was a moving exploration for those who took part. The recitations were layered to create a sound constellation in which words themselves and the coalescing of the language timbres created a sounded ‘wordless’ prayer. One participant suggested: “So this is what God must hear!’ The title Beyond Babel, is ironic in that different deep mother tongue words when combined become ‘wordless’ sounds and yet remain a prayer. The constellation was used in the departure scene in the Opus: Hiraeth, on exile and migration. Some of the individuals languages and the constellation can be heard here:

An Ecumenical Prayer for Pentacost

Psalmody

The HARK ekphrastic methodology was used to imagine a project, designed along the lines of the later lockdown composing project, of working with the Book of Psalms. We collected many examples of poetic renditions of Psalms covering almost all of the Book of Psalms (in the King James Bible), we proposed that a new Psalter be written, the St Andrews Psalter, which would be composed of editions of groups of psalms chosen by poets who would re-imagine the Psalm and also be paired with composers who would compose a chant for that psalm. 10 -15 psalms would be completed each year for 10 years and perfumed at an Annual Event in St Salvators Chapel. The poets would have the source material already gathered by HARK which is a compendium of all the poetic re-imaginings of psalms ranging from The Venerable Bede, through Sir Philip Sydney, John Keble to Christopher Hill.

This ekphrastic approach has also been considered as a way of working with local church congregations along the lines of the HARK Listening Groups where, through listening and reflecting (and possibly performing) a piece of music (for example the Strathclyde Motets by James Macmillan) a liturgical prayer/meditation could be created and performed in the actual liturgy.

Both of these projects await initiation.